Receptivity and offering: Regret

Lynne Baab • Thursday February 10 2022

“No regrets” is a quintessentially American approach to life, emphasized by famous Americans as diverse as Norman Vincent Peale and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and immortalized in song by musicians like Ella Fitzgerald and Eminem. However, this “no regrets” approach to life is an “unsustainable blueprint for living,” according to Daniel H. Pink, author of The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves us Forward.

An excerpt from Pink’s book was published recently in the Wall Street Journal, and I have pored over that excerpt because it spoke to me so strongly. Pink argues that “no regrets” is particularly inappropriate as we enter the third year of pandemic living. It would be cruel to tell a depressed teenager, an isolated senior, or someone who has lost one or more family members to covid that they should feel no regrets. Pink writes,

“For the last three years, I have examined several decades of research on the science of regret. At the same time, I have collected and analyzed more than 16,000 individual descriptions of regret from people in 105 countries who responded to my online survey invitation. One of them was Abby Henderson, a 30-year-old Arizonan, who wrote: ‘I regret not taking advantage of spending time with my grandparents as a child. I resented their presence in my home and their desire to connect with me, and now I’d do anything to get that time back.’ Rather than shut out this regret or be hobbled by it, she altered her approach to her aging mother and father and began recording and compiling stories from their lives. ‘I don’t want to feel the way when my parents die that I felt about my grandparents of “What did I miss?”’

“The conclusion from both the science and the survey is clear: Regret is not dangerous or abnormal. It is healthy and universal, an integral part of being human. Equally important, regret is valuable. It clarifies. It instructs. Done right, it needn’t drag us down; it can lift us up.”

I love what Abby Henderson did in response to her regret. I love the idea that regret clarifies and instructs. Clearly, from Abby’s story, regret also motivates and empowers.

Pink continues, “Granted, regret feels awful. . . . Regret hurts; it makes sense that we’d try to shut it out. But if it’s hard to take, it’s even harder to avoid.” The way he describes regret has so many parallels with my writing about grief. We don’t want to feel it. We wonder if we’re doing something wrong when we feel it. We try all sorts of consumption – such as shopping, food, alcohol, and thrilling experiences – to push both grief and regret down deep inside us so we don’t have to feel pain.

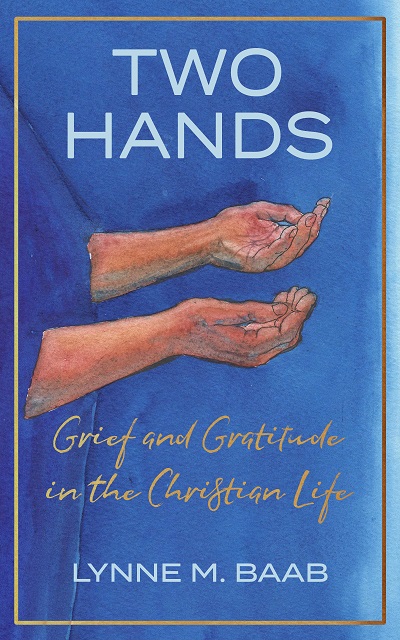

In fact, I would argue that regret is a form of grief. If our culture denies grief and gives us no handles on how to deal with it, the same would be true of regret. A major lesson of the pandemic for me is that no matter how much we affirm that grief is significant and needs to be expressed, it hurts. And hurts. And hurts. So if I’m right that regret is a form of grief, I guess I have to expect that it will hurt, too, as I grow in being honest about it and allowing it to clarify, instruct, motivate and empower me. Perhaps I can learn to hold in one hand the joy of learning from regret, while holding the pain of regret in the other hand, much as I have advocated holding grief and gratitude in two hands.

Christians can take comfort in the many psalms that model bringing all sorts of pain to God. We can also take comfort in watching Jesus engage with so many forms of human emotion and also express his own emotion honestly. We can also take comfort that the Holy Spirit uses so many components of everyday life to guide us. As a result of reading some of Daniel Pink’s work on regret, I want to learn the practice of offering my regrets to God, asking for the guidance and power of the Holy Spirit to transform them into appropriate and healthy action.

(Next week: steps in reckoning with regret. Illustration by Dave Baab: Mount Cook and Lake Pukaki, New Zealand. If you’d like to receive an email when I post on this blog, sign up below under “subscribe.”)

Some of my posts about grief and gratitude. I found it fascinating to re-read these and notice the ways the grief I describe has similar characteristics to regret:

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)