Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

Lynne Baab • Thursday November 1 2018

Through my childhood, in Episcopal and Anglican churches, incense played a role on special occasions. The priest would walk down the center aisle swinging a chain with a metal ball on the end. Inside the ball, incense was burning, and the smoke came out of cleverly shaped holes in the ball.

As I child, I was never sure if I liked the weird smell of incense. But it definitely signaled something about holiness to me.

Fast forward fifty-some years to the ordination of my colleague, James, to the Anglican priesthood. The ordination was held at St. Paul’s Anglican Cathedral in Dunedin, New Zealand, and during some of the prayers, James lay face down on the marble floor.

How are incense and laying face-down related? Both draw on images of prayer in the book of Revelation.

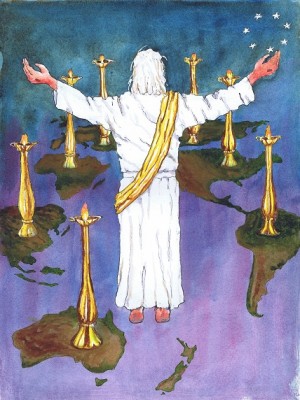

In Revelation 1, the writer, who identifies himself as John, says he was “in the spirit on the Lord’s day” (verse 10). He hears a loud voice, then turns and sees an extraordinary vision of Jesus standing among seven lampstands, with white hair, eyes of flame, feet like burnished bronze, a sword coming from his mouth, and seven stars in his hands (verses 12-16).

John says, “When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead” (verse 17). This posture of awe and submission is echoed in many ordinations in the Roman Catholic and Anglican traditions. I was privileged to see it when James was ordained.

Chapters 2 and 3 of Revelation contain the powerful letters to the seven churches of Asia Minor, Jesus’ confronting and comforting words that are still relevant today.

Revelation 4 describes a vivid scene of worship involving precious gems, thrones, flashes of lightning, a crystal sea, four strange creatures singing “Holy, holy, holy,” and 24 elders who “fall before the one who is seated on the throne” (verses 3-11). So again, worshippers are showing their devotion with their whole bodies in a position of submission, awe, and trust.

In Revelation 5 a drama unfolds. A scroll has been sealed with seven seals, and a mighty angel looks for someone worthy to undo the seals. No one in heaven or on earth is worthy, except for the Lion of the tribe of Judah, who is also the Lamb. As the Lamb takes the scroll, the four creatures and the 24 elders again fall before him and sing, each hold a harp and a golden bowl full of incense (verses 1-8).

The incense is identified as the prayers of the saints. In Revelation 8:4, incense is again connected with the prayers of the saints. In my childhood, when the incense was burned in church, I wish someone had told me about this symbolism.

Because of many excesses in the Roman Catholic Church of the late Medieval period, the Protestant Reformers tried to return to simple expressions of faith: grace alone, faith alone, the Bible alone as a source of authority. This was often accompanied by simplifying everything: no art in worship spaces, no incense, no laying face down during ordination services.

I’ve been heavily influenced by both the Episcopal/Anglican heritage of my childhood, and the grace-oriented, Bible-focused faith I learned in my early adult life in various Protestant settings, accompanied by very little art, incense or other sensory-focused experiences.

In recent years I’ve been asking myself this: What does a rich prayer life look like when it draws on all bodily senses? How can smells, taste, touch, bodily movements, and art contribute to prayer? How can we grow in bringing our whole bodies to God in prayer?

Revelation offers a few answers to my questions, and, as Revelation always does, raises yet more questions.

֍ ֍ ֍

Quick links:

- my latest book, Almost Peaceful: My Journey of Healing from Binge Eating

- last year's book, Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional, illustrated with Dave Baab’s beautiful watercolors

- my most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and Kindle)

- quick overview of all my books

- more than 50 articles I’ve written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

Illustration: Dave Baab’s interpretation of Revelation 1:12-16. Notice the seven lampstands, which Jesus in Rev 1:20 identifies as the seven churches. In the painting, Dave has broken up the continents and put one lampstand on each continent, symbolizing to Dave the reassuring reality that the church on every continent belongs to Jesus, and that Jesus will keep the light burning in and through his church throughout the earth. Also note the way Dave represented Jesus’ white hair, golden sash, bronze feet, and the seven stars in his right hand. I have the original of this painting hanging right beside my desk, reminding me that Jesus is Lord of the Church even in the midst of decline, scandal, conflict, and discouragement. Many times the painting has brought tears to my eyes.

If you'd like to receive an email when I post on this blog, sign up under "subscribe" in the right hand column of the whole webpage. Previous posts in this series:

Connections between the Bible and prayer

The character of God and prayer

The context of the Lord’s Prayer

Instructions from the Apsotle Paul

Paul's prayer in Colossians

Two prayers in Ephesians

The prayer in Philippians

Paul's thankfulness

A story of healing motivated by the instructions in James

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)