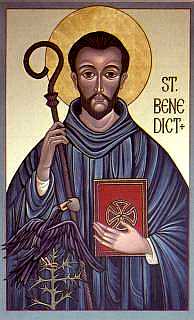

Benedictine spirituality: Who was Benedict?

Lynne Baab • Friday January 29 2016

Perhaps the current interest in Benedictine community living comes in part because of the parallels between Benedict’s time and ours. Benedict of Nursia lived from about 480 to 547, a time of affluence and sophistication in the Roman Empire. Wealth was used unscrupulously for personal political gain, the gap between the rich and the poor was widening, and the church was infected with controversy and political concerns. Child slavery, prostitution, oppression and injustice permeated society. Barbarian tribes from the north were migrating into the settled, agrarian lands of northern Italy, producing a multicultural society characterized by change and instability.

Our times are not much different.

In his early adulthood in Italy, Benedict became so disillusioned and disgusted with the affluence and decadence of his society that he withdrew to an isolated cave to live a solitary life of prayer. Other people soon joined him for many of the same reasons, and a monastic community began to grow. The Rule of St. Benedict was written to guide the community as its life developed.

The genius of Benedict’s Rule comes from its simplicity and its call back to the basics of scripture, prayer, solitude, community, and service, which transcend political turmoil and cultural upheaval. The Rule offers guidelines for ordinary people living ordinary lives. In the midst of the frenzy of twenty-first century life, the simplicity of Benedict’s priorities can enable us to center our lives in Christ in the midst of the many responsibilities, priorities and commitments that absorb us.

Benedict was by no means the first monk interested in monastic communal living. As early as the second century after Christ, individual Christians left the comforts and stresses of society to pursue a life of solitary prayer in the wilderness. When more Christians joined them, all the issues of community living presented themselves.

Benedict’s Rule was based on earlier writings that gave guidelines for communal Christian living. The Rule of St. Benedict has depth, balance, and a practical orientation that changed the face of spirituality in the Western half of the Christian world.

The Rule, a short book composed of a prologue and 73 brief chapters, addresses everyday topics: work, recreation, food, silence, rest, study, prayer, and the need to listen. There are some sections that proscribe discipline and daily routines in a way that is foreign to us, but much of the Rule is still applicable today for monastic living and presents significant insights even for those of us who are not called to a monastery.

Benedict lays out three monastic vows: stability, conversion of life, and obedience. All of these have practical application in everyday life for any Christian. Benedict believed that we have enough, that God has given us all we need for our daily lives, which helps us slow down our striving and enables us to look for God in the everyday aspects of our daily lives. Benedict calls us to the disciplines of prayer, self-examination, and confession, all of them exercised in community.

Esther de Waal, in Living with Contradiction: An Introduction to Benedictine Spirituality, writes about the impact of one of Benedict’s priorities:

If I try to follow St. Benedict I find that I have to think about the material things in my life, and that I am being called to establish a right relationship with all my possessions. I see myself as a steward, holding these things in trust, enjoying but not owning them. I find this easier to accept in theory than in practice. But when I do remind myself that all these good things belong to God and not to me, I find that my sense of gratitude for the extraordinary generosity of God brings with it also a sense of freedom. All things are on loan, all things come from God, and that includes my own body as well. I have no rights and I do not possess.

֍ ֍ ֍

Quick links:

- my latest book, Almost Peaceful: My Journey of Healing from Binge Eating

- last year's book, Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional, illustrated with Dave Baab’s beautiful watercolors

- my most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and Kindle)

- quick overview of all my books

- more than 50 articles I’ve written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

This is the third post in a series on Benedictine spirituality. The earlier posts were

Next week focuses on Benedictine spirituality for today. Excerpted from A Renewed Spirituality: Finding Fresh Paths at Midlife by Lynne Baab.

If you’d like to get an email when I post on this blog, sign up below under “subscribe.”

For further reading:

Paul Wilkes, Beyond the Walls: Monastic Wisdom for Everyday Life (New York: Doubleday, 1999).

Timothy Fry, OSB, editor, The Rule of St. Benedict in English (Collegeville, Minn,: The Liturgical Press, 1981).

Elizabeth Canham, Heart Whispers: Benedictine Wisdom for Today (Nashville: Upper Room, 1999).

Esther de Waal, Living with Contradiction: An Introduction to Benedictine Spirituality, (Harrisburg, Pa.: Morehouse, 1989, 1997).

Kathleen Norris, The Cloister Walk (New York: Riverhead Books, 1996).

Dennis Okholm, Monk Habits for Everyday People: Benedictine Spirituality for Protestants (Grand Rapids: MI: Brazos Press, 2007).

Gifts of Freedom: The Sabbath and Fasting, article by Lynne Baab that draws on her monastery visits.

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- March 2026 (2)

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)