Chinese New Year: A Case Study for Shifts in Christian Caring

Lynne Baab • Wednesday February 6 2019

Perhaps you’ve met someone of Chinese descent or someone from China. If so, you’ll know that Chinese New Year is a really big cultural celebration, sort of like Christmas, Thanksgiving and New Years rolled into one big, long holiday with lots of food and family time. The date changes each year based on the lunar calendar, and this year Chinese New Year is February 5.

A friend of mine who lived in China told me that the holiday lasts two weeks, with the first four to five days being an intense time of visiting with family and friends. Traditionally, the preparation for the holiday included cleaning the house and replacing the food for the kitchen gods at the family altar.

I learned about Chinese New Year in New Zealand – where I was migrant – from Malaysian students of Chinese descent – whose ancestors were migrants from China to Malaysia and who were themselves migrants from Malaysia to New Zealand.

Christian ministry in the 21st century has some new aspects, as a big rise in world-wide migration is changing the demographics of our communities and our congregations. In 2017, to love our neighbor must include paying attention to the culture of origin of the people we want to extend care to. When we make friends with people from China or of Chinese descent, that means learning about Chinese New Year and what it means to them.

I want to compare and contrast two ways of attempting to show love to people who come from different countries or ethnicities. One way is to work on being “color blind,” where we focus on what we have in common and do our best to ignore differences in skin color or other differences that come from our ethnic backgrounds.

Paula Harris, a speaker and writer, was raised as a missionary kid, and her parents encouraged her to be color blind, which she views as a loving approach. In Being White: Finding our Place in a Multiethnic World, she describes how she became aware of the significance of ethnicity and what it means to people who live as minorities or migrants.

Harris came to understand that being color blind is good, but inadequate. She and her co-writer, Doug Schaupp, give six reasons why developing an appreciation for ethnicity reflects God’s values. Harris and Schaupp write that colorblindness:

- ignores the heart language of our ethnic minority friends;

- misses kingdom riches God intended for our blessing;

- misses who people really are at their core;

- assumes everyone is “white like me”;

- makes us vulnerable to stumbling into an Acts 6 rift; and

- numbs our hearts to the suffering of our friends. [1]

This year I invite you to have a conversation with any people from China or of Chinese descent that you know. Ask them about Chinese New Year. What do they like best? What did it mean to them as a child? What are their plans for this year? What did they do last year?

If your friends are Christian, ask some additional questions about where they see God’s grace and joy in the festivities. Perhaps the fresh start implied in Chinese New Year makes them think of the fresh start we have in Christ. You could ask about this.

Around the world, the number of people who do not live in their country of birth has increased to a sum larger than the population of Brazil. In addition, many people are second or third generation immigrants, who have retained holidays and practices rooted in the country of their ancestry. In many countries, indigenous people have cultural traditions, as do many African American people in the United States.

We can try to ignore cultural differences, or we can work on learning about them, affirming them and appreciating what they mean to people we care about. I’m trying to do more of the latter as a spiritual practice that I hope reflects the love of God.

I develop these ideas further in my recent book, Nurturing Hope: Christian Pastoral Care in the Twenty-First Century. I discuss shifts in Christian caring in recent years in the light of world-wide migration.

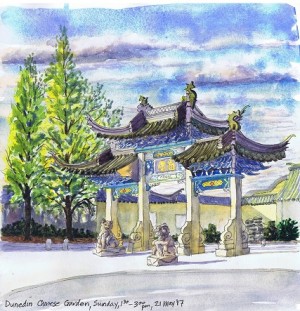

(Next week: Bishop Aiden of Lidisfarne. Illustration: The Chinese Gardens in Dunedin, New Zealand by Dave Baab. If you’d like to receive an email when I post on this blog, sign up under subscribe in the right hand column of the web page. This post appeared on the Godspace blog for Chinese New Year last year.)

Here's article I wrote that discusses the kind of listening skills that help us understand across cultures: To be a neighbor must include listening. It won an Australian Press Award.

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)