Grief AND thankfulness: What I learned from writing this series

Lynne Baab • Thursday February 13 2020

My husband Dave and I were talking about this series of blog posts, and he said, “You know, every single day there are things I grieve and things I’m thankful for. . . . Every day.” I agreed with him, and then I began wondering, why does this feel so revolutionary?

This series of posts has revealed my deep-seated adoption of a set of values – from my parents and from the wider culture – that have been destructive to me. My thinking has been skewed my whole life. I truly believed my parents’ approach to life: if you do things right, everything will work out well.

My dad used the word “incompetent” as a noun, and he talked about most politicians as “incompetents.” Everything would be much better in the world if “those incompetents would only do it this way. . . .” My mother was more interested in the social realm, and she taught me all sorts of social skills, and communicated many social values, that she believed would make life go well.

My grandfathers died when I was 7 and 15, so we experienced a bit of sadness. We moved almost every year because of my dad’s military career, and I was allowed to feel sad about that. But other than those hard things, every other hard thing, my parents seemed to believe, was caused by someone’s wrong choice which could be fixed. There was no room for sadness. All discussion and action should focus on figuring out the right behavior so everything would be okay.

As a teenager, I read Seventeen magazine religiously, poring over the very thin and beautiful models. If only I could look like them, I believed, then I would be happy. Sure, I grew up and left my parents’ home and stopped reading Seventeen. I attempted to figure out new values to live by. But that can-do, problem-solving spirit that my parents emphasized continued to shape me. And I continued to see countless advertisements that advocated beauty and material possessions as the solution to any kind of personal pain.

In addition, the American culture has an obsession with optimism, which has only gotten worse over my lifespan. Be positive, work through the pain, keep going, don’t think about negative things, don’t feel sad emotions.

On some level, for most of my adult life, I have believed there are easy answers to most problems, and that when things aren’t going right in my life, it must be my fault. I should fix something, buy something, or have a better attitude. This is a heavy burden to bear. How much better to rest in the God who grieves with us when things don’t go well for such a variety of reasons beyond our control.

As I have written about grief, I have come face to face with how little power each of us has to change people and situations beyond ourselves – and hey, even changing ourselves isn’t easy a lot of the time. Real life situations are often so complicated that solutions aren’t clear-cut. And even when solutions seem obvious, opposing interests – both in the outside world and within our own minds and bodies – complicate the implementation of change. I grieve at the intractable problems that damage human beings and the earth in so many ways.

The world is a scary place. Maybe my parents’ myth of control was a way of comforting themselves in complex and worrisome situations. Maybe the Depression and World War 2 shaped them so profoundly that their strategies were necessary for coping. I want to feel grace toward them, while choosing a different path.

I want to be a person who can feel sadness without blaming myself for doing something wrong. And I want to accept God’s forgiveness when I have done something wrong. I want to be a person who is thankful for God’s abundant gifts, while also feeling the lacks and pain in my life and other people’s lives. I want to grieve honestly in the presence of Jesus and receive the comfort of the Holy Spirit.

I want to trust in the God who made me, saved me, loves me, and provides for me. I want to trust that Jesus is beside me, in good times and hard times. And I want to feel God’s joy with me as I rejoice in the gifts of life.

To all of you who gave me feedback on this series, thank you. It’s been a joy to write it and a joy to hear its impact on you, my valued readers.

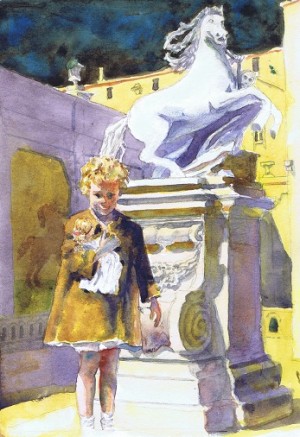

Next week: an important 2020 anniversary, the beginning of Prohibition in the United States in 1920 and what we can learn from it. Illustration by Dave Baab: me at three and a half. I welcome new subscribers. If you’d like to receive an email when I post on this blog, sign up below.

This is the 15th and last post in a series on grief AND thankfulness. The first posts is here, and the other posts follow sequentially afterward.

My book on this topic – Two Hands: Grief and Gratitude in the Christian Life, now available as an audiobook as well as paperback and kindle.

Two options for Lenten devotionals (Lent begins February 26 this year):

- Creation care as a hopeful spiritual practice in Lent – an online devotional I co-wrote last year for my own church

- Draw Near (available for free download as a pdf), which I wrote and my husband Dave illustrated. Each day of Lent has a psalm for you to ponder, with questions for reflection/discussion.

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)