Receptivity and offering: Reasonable hope

Lynne Baab • Thursday January 27 2022

Back in 2013 I attended a seminar about mind-body connections, and I learned the significance of the words we use out loud or in our thoughts and prayers. According to the leader of the seminar, when I pray, “God help me with my anxiety,” or when I refer to anxiety in a conversation, I reinforce the neural pathways related to anxiety. Talking about my desire as “freedom from anxiety” has the unintended consequence of lighting up neurons related to anxiety. When I pray, “God give me peace,” I reinforce brain pathways related to peace, and these life-giving neural pathways are beneficial to me and to others.

I have mentioned before that hyper-optimism in my family of origin was highly toxic to me, and I developed a commitment to honesty about how I was feeling. The 2013 seminar was truly mind-blowing because I had to try to integrate my commitment to honesty with my desire to live in a way that embraces God’s shalom. I came to realize that “God, I need your peace” is just as honest as “God, I feel anxious right now.”

Last week I came across an article about the way that the words we say change the structure of our brain. I posted the article on Facebook and asked the question: “When does choosing positive language flip over into toxic positivity and denial?” Numerous people responded.

One of my friends mentioned her son’s treatment for a head injury. The neurologist told the family to inquire, “How is your recovery today?” rather than asking how his head pain is today. A spiritual director and former prison chaplain talked about her pleasure in honesty and her dislike of “dishonest words coated in sugar.” She said she listens for people’s “hidden story, or the more hopeful story, that could be called positive.” She desires to help each person bring those stories to the surface. Another friend talked about the solace of having someone be present with you in pain, without “feeding delusions, false hopes and fears.” She mentioned the term “reasonable hope,” which seems to be a lovely contrast to delusions and false hope.

One of my friends lives in Oregon where a huge forest fire swept through 18 months ago and burned her house to the ground. She wrote: “As one who fairly recently experienced a devastating event, I had choices of how to live with it. I have the option to be angry, to blame others (and certainly there are many who are blaming government officials for more than what they might be culpable for) and be bitter. But . . . will that bring back my burned out house and all of the ‘stuff’ that burned up? No. Was it my fault? No. Did God smite me? No. Was it the governor's fault? No. So what is my response? To be thankful for what I have – family, a view of our river (although it looks quite a bit different with so much green gone), and to truly understand what it is to store up riches in heaven where moths and rust cannot destroy. I see other people in my area who are angry and bitter and soooo sad, but I can't live there. I feel fleeting sadness when I think of some possessions that I lost (that were received in special times or were from past generations) but in the end, they were just things. People have said that they admire my attitude – but I really am grateful for what I have, who I know, and that God walks with me through difficult times. I guess if I denied any sadness, it might slip over to toxic positivity.”

I hear “reasonable hope” in her words, a term coined by psychologist Kaethe Weingarten. She writes that “reasonable hope’s objective is the process of making sense of what exists now in the belief that this prepares us to meet what lies ahead.” She describes reasonable hope as a practice, a way of affirming that we have influence on future events even while we also know the future is uncertain. Reasonable hope accommodates doubt, contradictions and despair. This term helps me make sense of my journey. I had to learn that dwelling in negativity (because it’s honest!) is not the best reaction to toxic optimism. Reasonable hope is an equally honest response, because God is still at work in our world, and reasonable hope is so much healthier for my inner being than focusing endlessly on sad and hard emotions.

Reasonable hope is also a good choice in conversations because it benefits others, not just ourselves. Lisa Feldman Barrett, professor of psychology at Northeastern University, describes the ways that our choice of words influences others:

"The power of words over your biology can span great distances. Right now, I can text the words ‘I love you’ from the United States to my close friend in Belgium, and even though she cannot hear my voice or see my face, I will change her heart rate, her breathing, and her metabolism. Or someone could text something ambiguous to you like, ‘Is your door locked?’ and odds are that it would affect your nervous system in an unpleasant way. Your nervous system can be perturbed not only across distances, but also across the centuries. If you've ever taken comfort from ancient texts such as the Bible or the Koran, you've received body-budgeting assistance from people long gone. Books, videos, and podcasts can warm you or give you the chills. These effects might not last long, but research shows that we all can tweak one another's nervous systems quickly with mere words in very physical ways that go beyond what you might suspect." [1]

In 2022, may we offer our words of reasonable hope to God, ourselves and others. May our reasonable hope be based in the love we receive from God.

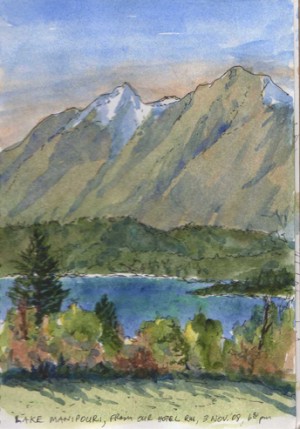

(Next week: “another world walking beside ours.” Illustration by Dave Baab: Lake Manapouri, New Zealand. I love getting new subscribers. Sign up below under “subscribe” to receive an email when I post on this blog.)

One strategy for growing in reasonable hope is to hold grief and gratitude in two hands. Check out my new book on that topic.

Another strategy for growing in reasonable hope is to learn to separate thoughts from feelings. Here are the posts I wrote about that how and why to do that:

- Separating thoughts from feelings

- Feeling the feelings using the RAIN process

- Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- Is self compassion appropriate for Christians?

- A Christian perspective on thoughts

[1] Lisa Feldman Barrett, "The Power of Words" on Maria Shriver's blog.

Next post »« Previous post

Subscribe to updates

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Lynne M. Baab, Ph.D., is an author and adjunct professor. She has written numerous books, Bible study guides, and articles for magazines and journals. Lynne is passionate about prayer and other ways to draw near to God, and her writing conveys encouragement for readers to be their authentic selves before God. She encourages experimentation and lightness in Christian spiritual practices. Read more »

Quick links:

- Two latest books: Draw Near: A Lenten Devotional and Friendship, Listening and Empathy: A Prayer Guide (illustrated with Dave Baab's beautiful watercolors)

- Most popular book, Sabbath Keeping: Finding Freedom in the Rhythms of Rest (audiobook, paperback, and kindle)

- quick overview of all Lynne's books

- more than 50 articles Lynne has written for magazines on listening, Sabbath, fasting, spiritual growth, resilience for ministry, and congregational communication

You can listen to Lynne talk about these topics:

"Lynne's writing is beautiful. Her tone has such a note of hope and excitement about growth. It is gentle and affirming."

— a reader

"Dear Dr. Baab, You changed my life. It is only through God’s gift of the sabbath that I feel in my heart and soul that God loves me apart from anything I do."

— a reader of Sabbath Keeping

Subscribe

To receive an email alert when a new post is published, simply enter your email address below.

Featured posts

- Drawing Near to God with the Heart: first post of a series »

- Quotations I love: Henri Nouwen on being beloved »

- Worshipping God the Creator: the first post of a series »

- Sabbath Keeping a decade later: the first post of a series »

- Benedictine spirituality: the first post of a series »

- Celtic Christianity: the first post of a series »

- Holy Listening »

- A Cat with a Noble Character »

- Welcome to my website »

Tags

Archive

- March 2026 (2)

- February 2026 (2)

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (6)

- November 2025 (4)

- October 2025 (3)

- September 2025 (5)

- August 2025 (4)

-

July 2025 (6)

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying about AND — again

- Praying about the flow of time: Praying for our ordinary lives

- Praying about the flow of time: Wind and water

- Praying about the flow of time: Paying attention to our stories

- What I learned from the past year's blog posts

- First post in a new series: Journey

- June 2025 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (5)

- February 2025 (4)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (3)

-

November 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Small actions with big benefits

- Praying about the flow of time: The overlap of the sacred and the ordinary

- Praying about the flow of time: The joy of the kingdom of God

- Praying about the flow of time: Advent can be confusing

- Praying about the flow of time: Why Jesus had to come

-

October 2024 (5)

- Praying about the flow of time: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Praying about the flow of time: A month of celebrating renewal and moral responsibility

- Praying about the flow of time: The Feast of Tabernacles calls us to stay fluid and flexible

- Praying about the flow of time: Daily rhythms of prayer

- Praying about the flow of time: All Hallows Eve and All Saints Day

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (5)

- July 2024 (3)

- June 2024 (5)

- May 2024 (5)

- April 2024 (4)

-

March 2024 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about distractions from empathy

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to keep empathy flowing

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Everyday initiative

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for guidance for ending conversations

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Reflecting on the series

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

-

December 2023 (6)

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Initiating

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying about listening roadblocks

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to love the poverty in our friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy curiosity”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying for “holy listening”

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Praying to give affection extravagantly

- November 2023 (4)

-

October 2023 (5)

- Friendship, loneliness and prayer: A listening skill with two purposes

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Saying “thank you” to friends

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: One more way reflecting helps us

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Lessons from two periods of loneliness

- Friendship, loneliness, and prayer: Types of reflecting, a listening skill

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (4)

- July 2023 (5)

- June 2023 (3)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (5)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (5)

- September 2022 (5)

-

August 2022 (6)

- Draw near: Confessing sin without wallowing

- Draw near: A favorite prayer about peace, freedom, and much more

- Drawing near with Desmond Tutu: God’s love is the foundation for prayer

- Draw near: Worshipping God with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Yearning, beseeching and beholding with Desmond Tutu

- Draw near: Praising God with Desmond Tutu

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (6)

- May 2022 (5)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (5)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (3)

- December 2021 (5)

- November 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (5)

- September 2021 (4)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (5)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (5)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (5)

- September 2020 (4)

- August 2020 (4)

- July 2020 (5)

- June 2020 (4)

-

May 2020 (4)

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of separating thoughts from feelings

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of welcoming prayer

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: a kite string as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of God’s distant future

-

April 2020 (7)

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: the lifeline of God’s constancy

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of accepting my place as a clay jar

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of memories

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of “Good” in “Good Friday”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of “easier does not mean easy”

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: The lifeline of nature

- Spiritual diary of sheltering in place: the lifeline of God’s voice through the Bible

-

March 2020 (7)

- Important anniversaries in 2020: The first Earth Day in 1970

- Important anniversaries in 2020: Florence Nightingale was born in 1820

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Weeks 1 and 2

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: God's grace as a lifeline

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: The lifeline of limits on thoughts

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Wrestling with God for a blessing

- Spiritual diary of self-isolation: Responding to terror by listening to Jesus voice

- February 2020 (4)

- January 2020 (5)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (5)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- May 2019 (5)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (4)

-

January 2019 (5)

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Jesus as Friend

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship with Christ and friendship with others

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Who is my neighbor?

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Friendship as action

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Hymns that describe friendship with God

- December 2018 (3)

-

November 2018 (5)

- Connections between the Bible and prayer: Sensory prayer in Revelation

- First post in a new series: Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Strong opinions and responses

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: My conversation partners about friendship

- Nurturing friendships in a cellphone world: Two views about communication technologies

- October 2018 (4)

- September 2018 (4)

-

August 2018 (5)

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time

- Providing Christian care in our time: Seven trends in pastoral care today

- Providing Christian Care in Our Time: Skills for Pastoral Care

- Providing Christian care: The importance of spiritual practices

- First post in a new series: Connections between the Bible and prayer

- July 2018 (4)

- June 2018 (4)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (4)

- March 2018 (5)

- February 2018 (4)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (5)

- November 2017 (4)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (4)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (4)

-

May 2017 (5)

- My new spiritual practice: Separating thoughts from feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Feeling the feelings

- My new spiritual practice: Coping with feelings that want to dominate

- My new spiritual practice: Dealing with “demonic” thoughts

- My new spiritual practice: Is self-compassion really appropriate for Christians?

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (4)

- December 2016 (5)

- November 2016 (4)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (5)

- August 2016 (4)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (5)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (5)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (4)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (5)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (4)

- May 2015 (4)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (4)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (5)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (4)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (5)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (7)